“There is no education like adversity”: learning from the positive experiences of lockdown

As Disraeli once wrote “there is no education like adversity”, a maxim that seems just as relevant during the current pandemic crisis as when it was first penned a century and a half ago. In this blog we consider what can be learnt from the positive experiences of home learning for some children and families during lockdown.

Dr Noel Purdy is Director of the Centre for Research in Educational Underachievement at Stranmillis University College, Belfast.

Alistair Hamill is Senior Leader in Lurgan College, responsible for Teaching & Learning, and Learning Lead in Craigavon Area Learning Community.

There is now a wealth of evidence from studies here in Northern Ireland (Walsh et al., 2020, O’Connor et al., 2020) across the rest of the UK (Sutton Trust, 2020; IFS, 2020), in the Republic of Ireland (Mohan et al., 2020) and further afield (Goldstein, 2020), that lockdown has been very challenging for many children and for their parents/carers, often leading to an exacerbation of existing social inequalities (Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 2020; ONS, 2020) and widely divergent educational experiences.

Among those most likely to be negatively impacted have been those from lower socio-economic backgrounds, those with special educational needs and those in rural areas with poor internet connectivity (Walsh et al., 2020; O’Connor et al., 2020). Most of our attention has now justifiably turned towards planning for what has been referred to as a flexible ‘recovery curriculum’ to prioritise emotional wellbeing needs, to redress the imbalance of educational access and to bridge the learning gap which will inevitably have widened during lockdown.

However, it is important to acknowledge that there have also been some children who have had overwhelmingly positive experiences of learning at home since March, and we argue here that there is also an onus on schools to meet their needs during the Restart and, where possible and appropriate, to seek to learn from and use their positive experiences to promote better learning dispositions among the wider peer group.

Many families have enjoyed home learning

First, and most broadly, the findings of the CREU online parental survey carried out in April/May highlight that for a sizeable minority of families, the experience of home learning has been enjoyable, offering them an opportunity to spend more time together, enjoying a calmer pace of life, giving parents time to engage confidently and more directly than ever before in their children’s learning, supported by appropriate online resources from the school, while also giving children more time to play, relax and enjoy the outdoors. Indeed this resonates with a recent UK-wide study where 26% of parents reported that their relationship with their children had improved during lockdown (especially where the youngest child was under 4 years old) and only 4% said the relationship had worsened. In open-ended comments from the Stranmillis CREU study, several parents also commented specifically on how their children were really enjoying the home-schooling experience (though often missing their friends and classmates), feeling less stressed by the pressure of external exams, benefitting from a ‘slower pace of life’, and enjoying opportunities to re-connect as a family:

The difference in our kids is amazing they are so much happier and more relaxed the whole house is much less stressed, adults included.

I think my children have coped very well – they are settled, contented and enjoy the cocoon of home.

It has given my children more time to play freely which is positive.

My son suffers with anxiety at school and with being at home with the lockdown I find it really has helped my son focus more on school work and not the class clown or feeling anxious or worried so he definitely seems more relaxed and has the head space to study better with less stress

Some children with ASD and ADHD are benefitting

Second, and more specifically, while it has been noted by NICCY and others that many children with special educational needs have undoubtedly struggled with the lack of additional learning support, therapeutic intervention, familiar structure, leisure and respite opportunities, conversely a smaller number of other children with special educational needs have actually thrived. Some parents in the CREU survey spoke of children with ASD and ADHD in particular whose anxiety levels have fallen, free from the social pressures of a busy school environment, away from the threat of bullying, and able to learn in a less regimented, more flexible and secure home environment:

Our son has Aspergers. He is v bright but lacks concentration. When he is in the mood to do work, we do it. He needs a lot of attention to keep him in tasks. Generally speaking he is much less anxious than when at school, he struggles with the social side of school which results in massive anxieties and OCD behaviours. These have significantly reduced since he has been at home.

My child is currently being assessed for ADHD which does at time impact her focus and motivation and I feel she has enjoyed the flexibility/autonomy of our lessons.

I think my dyslexic son benefits as he doesn’t have the same pressures as the classroom and I can work with him 1-1 and produce much better work than when he is in a class of nearly 30 pupils. I can also work one on one to improve his attention issues.

Remote learning has benefits for pupil self-regulation

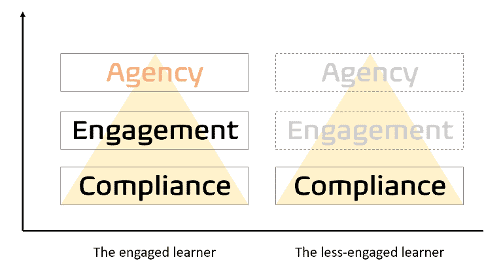

Third, lockdown has highlighted the importance of self-regulation among learners. Schools provide a highly structured, regulated environment, with a high degree of timely accountability for the pupils as they do their work. For pupils who struggle with self-regulation, this environment can, at the very least, produce compliant learners: pupils who will turn up to class, generally do the work set by the teacher and mostly hand work in on time. In the lockdown environment, the loss of the direct experience of this structure, regulation and accountability has left pupils with much more freedom – and responsibility – to self-regulate. A recent ETI report found that many post-primary pupils struggled even with basic levels of compliance in this context, but there is evidence that other pupils managed this freedom very well, supported by learning resources from, and interactions with, their teachers. More significantly, there is evidence from studies such as a recent school-based study in the Netherlands that learners who can self-regulate go on to achieve more highly.

So, what are the qualities exhibited by such pupils and what can we learn from them? An Education Endowment Foundation report summarises the evidence on self-regulation and metacognition, and cites a range of strategies that help pupils learn independently, including: ‘setting specific short-term goals, adopting powerful strategies for attaining the goals, monitoring performance for signs of progress, restructuring one’s physical and social context to make it compatible with one’s goals; managing time-use efficiently; self-evaluating one’s methods; attributing causation to results and adapting future methods’.

Based on the additional experience of online teaching of 14-18 year olds in one local grammar school during lockdown, it has become clear that some pupils, especially those in KS4/5, have developed sufficient self-regulation skills not only to comply with the work set, but to become fully engaged in their learning. More than that, it has given some pupils a high degree of agency in their own learning, as they have shown significant self-awareness to adapt their learning schedules and strategies based on self-reflection to align with how they learn best. These include pupils who have designed their own learning timetable for the week, using the learning support from the school as a foundation, but adapting it, based on a high degree of self-awareness, to best facilitate their own learning.

Looking ahead we would recommend that schools seek to do more to develop self-regulation skills among pupils, a view echoed by the EEF, whose report on remote learning published at the start of lockdown, made the following recommendation:

Supporting pupils to work independently can improve learning outcomes. Pupils learning at home will often need to work independently. Multiple reviews identify the value of strategies that help pupils work independently with success … Wider evidence related to metacognition and self-regulation suggests that disadvantaged pupils are likely to particularly benefit from explicit support to help them work independently, for example, by providing checklists or daily plans.

With the possibility of further school disruptions in the 2020/21 school year, the need to train pupils in self-regulation skills early upon their return to school is imperative.

Learning from lockdown

As schools transition back to a blended model of face to face and remote learning, how do we respond to what has been learnt from this time? The following questions might facilitate some self-reflection for teachers, school leaders and policy-makers:

1. How do we ensure that our approach to education after lockdown is more balanced?

In what ways can we make school less pressured, more pastoral, less assessment-driven and more focused on the well-being of individual children, while recognising the potential to build on positive experiences of family and parental engagement since March? How do we prioritise relationships – within schools, within families and between schools and families?

2. How do we best prepare some of most vulnerable learners with special educational needs for the return to school in August/September?

It must be acknowledged that this will not be a return to school as they knew it before, and that during the last few months, new routines will have become established in settled home environments where face-to-face social interaction and communication could be kept to a minimum. How do we ensure that these pupils’ anxiety at the prospect of the Restart is minimised, and that school itself is a safer, happier place for all learners, irrespective of their needs?

3. How do we best support the full range of pupils’ self-regulation habits as schools open more widely?

How do we find ways of fostering and encouraging the continued growth of effective self-regulation shown by some pupils? In what ways do we ensure that the re-introduction of the highly structured environment of school does not cause them to lose the agency they have developed during remote learning? How can we find ways of sharing this effective practice with those pupils who have struggled more with this, encouraging them to learn from the example of their peers? And, how do we explicitly teach and upskill all pupils in the learnable techniques of self-regulation and metacognition?

We not have not sought here to deny or minimise the reality of the challenges faced by many children and their parents during lockdown (and these have already been well documented). Instead we set out to look for learning opportunities as a result of positive experiences where they did occur, despite adversity. In reporting these here, we hope to have provided some encouragement, though also many further questions to consider together over the coming days. In so doing, we have every confidence in the educational workforce of Northern Ireland to rise to the challenges that lie ahead.

Reasons to study at Stranmillis

Student Satisfaction

Stranmillis is ranked first in Northern Ireland for student satisfaction.

Work-based placements

100% of our undergraduate students undertake an extensive programme of work-based placements.

Study Abroad

All students have the opportunity to spend time studying abroad.

Student Success

We are proud to have a 96% student success rate.