Bridging the Lockdown Learning Gap (Part One)

Dr Noel Purdy is Director of the Centre for Research in Educational Underachievement at Stranmillis University College, Belfast.

Last Friday afternoon (5th June 2020) 369 educators from across Northern Ireland took part in a ground-breaking webinar on the theme of ‘Charting the Way: Conversations on education in NI ahead of September 2020’. It was by far the largest and most relevant-to-practice webinar on which I have ever had the privilege of being a panellist, and is a remarkable testament to the innovation of the @Blended_NI team who organised it in less than a week. In its sheer scale, it was also a clear sign of the thirst among dedicated classroom teachers for practical guidance, support and reassurance as they face the challenge of an educational earthquake (revolutions are planned after all) that no one could have predicted even six months ago. The webinar discussion was wide-ranging but one of the key issues to emerge was the likelihood of a ‘lockdown learning gap’ arising from the current pandemic crisis during which the vast majority of children are not being educated at school.

In response I would suggest that there are three key questions to consider: (1) Is there a lockdown learning gap? (2) What does the lockdown learning gap look like? and (3) What steps can we take to bridge the lockdown learning gap? In the first instalment of this blog I will address questions 1 and 2. In the second instalment I will consider question 3.

Is there a lockdown learning gap?

The short answer to this is that we can’t know yet for sure, as we don’t have reliable evidence from large-scale assessment tests to tell us the long-term impact. That will doubtless come over the coming months. In the meantime, we can however look at likely indicators from a number of recent studies: for instance, the pre-lockdown Ofcom survey revealed that online access is mediated by family background and that children in working class homes are less likely than those in middle class homes to access the internet via either a tablet (59% vs. 72%) or a mobile phone (49% vs. 62%); the early-lockdown Sutton Trust Report in April confirmed what I had predicted in an earlier blog that the lockdown has exacerbated existing inequalities in our education system with children from poorer backgrounds having less access to online resources and parental support, spending less time learning, and submitting less work than their less disadvantaged peers and those attending private schools. A month later, a report by the Institute of Fiscal Studies found that children from better-off families are spending 30% more time on home learning each week (amounting to more than two additional school weeks in total, assuming schools re-open here in late August/September) and have more access to individualised online resources than those from poorer families.

On 20 May our own Stranmillis report on Home-Schooling in Northern Ireland during the COVID-19 Crisis reported on a survey of over 2000 parents and found wide disparities in parental experiences of home-schooling, often mediated by their level of education and employment status. Experiences ranged from, on the one hand, confident, highly educated parents relishing the opportunity to spend more time learning alongside their children, safely cocooned from the pandemic threat, to, on the other hand, highly stressed working parents struggling to access resources, lacking confidence in their own abilities and battling to motivate their children to engage in learning during the ‘nightmare’ of lockdown. Based on these robust research reports, it is clear that there will undoubtedly be a lockdown learning gap. I would further suggest that the gap is likely to be wider than the traditional loss of learning experienced during the summer months, because unlike the normal two-month summer vacation, there will not have been such widely divergent experiences between children who have effectively been home-tutored by degree-educated parents and children who, through no fault of their own, have engaged in little or no learning at all.

What does the lockdown learning gap look like?

A report published earlier this month by the Education Endowment Foundation has attempted to predict the impact of school closures on the attainment gap, based on a rapid evidence assessment of a total of 11 previous studies of learning loss carried out since 1995. The EEF predictions suggest that the current closures will widen the attainment gap between disadvantaged children and their peers by a median estimate of 36% (with a range between 11% and 75%). The authors acknowledge the limitations of their review which (inevitably) is based on studies of summer learning gaps rather than the experiences of previous current pandemic crises. The report notes that sustained effort will be required over the coming months to help disadvantaged pupils catch up.

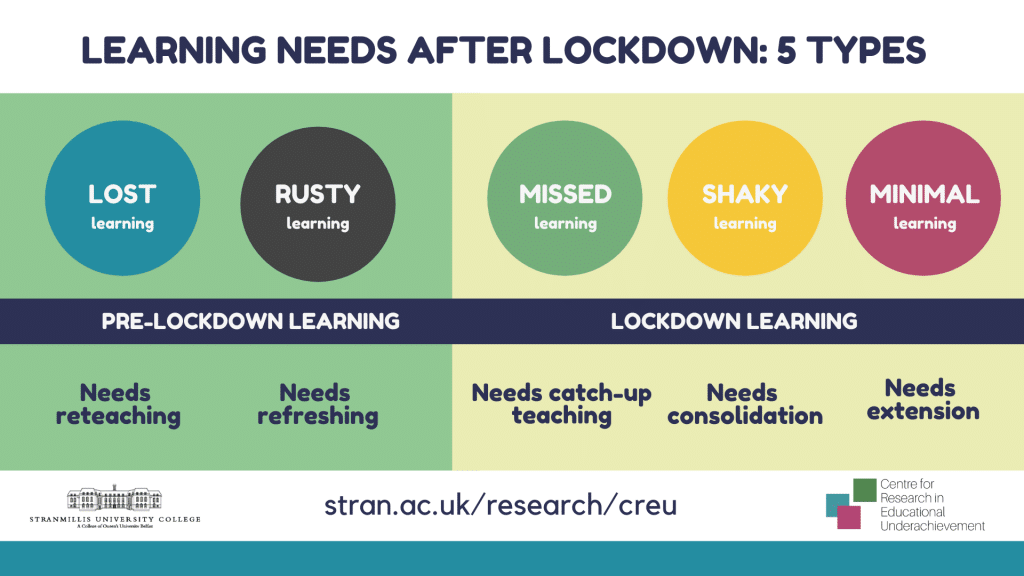

There has been much general discussion of learning needs but little specific about the particular learning needs of pupils on their return to school. Consequently, I have developed a typology of learning needs (see below), beginning with the need for teachers to address pre-lockdown learning which may be lost (and needs reteaching) or rusty (and needs refreshing) as might be expected after a lengthy break from traditional schooling of 5 months. This experience is similar to what might normally be expected following the summer vacation, and teachers are already skilled at recapping and refreshing knowledge and skills in September before moving on to new learning material.

A typology of lockdown learning needs

While this might represent relatively familiar ground for teachers, the particular features of lockdown learning loss are different: based on the studies cited above, we can also expect many children to have missed lockdown learning where there was little or no engagement at all with learning activities since March (through no fault of their own) and where catch-up teaching is required; shaky lockdown learning (requiring consolidation) where lockdown learning has been partial, incomplete or insecure, the result of a range of possible factors including poor or miscomprehension, lack of pupil motivation, inadequate parental support, and limited opportunities for individualised teaching and/or feedback; and minimal lockdown learning (needing extension) where learning has been rudimentary, covering minimum content but falling short of the wealth of differentiated extension activities that would normally have been provided in school.

The fundamental consequence of this is that additional time and investment will undoubtedly be required to identify and address the various learning needs of individual pupils over the coming months. So let’s not imagine for a moment that this is going to be ‘business as usual’ in August/September. With the prospect of widely divergent attainment levels following more than three months of widely divergent home learning experiences, teachers will need to draw on all of their professional expertise to meet the challenges ahead.

So, I would argue that there will undoubtedly be a lockdown learning gap come August/September, and that it will be wider than what might be experienced after the customary two-month summer vacation. Furthermore, I would contend that the nature of the learning deficit will be more varied and differentiated than ever before, including lost, rusty, missed, shaky and minimal learning, all of which need to be addressed by professional, dedicated and compassionate teachers. In the second instalment of this blog, I will consider the third and most significant key question: what steps can we take to bridge the lockdown learning gap?

Reasons to study at Stranmillis

Student Satisfaction

Stranmillis is ranked first in Northern Ireland for student satisfaction.

Work-based placements

100% of our undergraduate students undertake an extensive programme of work-based placements.

Study Abroad

All students have the opportunity to spend time studying abroad.

Student Success

We are proud to have a 96% student success rate.