Six months have now passed since the publication on 1 June 2021 of A Fair Start, the final report and action plan of the Expert Panel on Educational Underachievement in Northern Ireland. The panel members were Dr Noel Purdy, Director of the Centre for Research in Educational Underachievement, Stranmillis University College; Joyce Logue, Principal of Longtower Primary School, Derry/Londonderry; Mary Montgomery, Principal of Belfast Boys’ Model School; Kathleen O’Hare, former Principal of St Cecilia’s College, Derry/Londonderry and Hazelwood Integrated College, Belfast; Jackie Redpath, Chief Executive, Greater Shankill Partnership; and Professor Feyisa Demie who supported the panel in a research capacity. A Fair Start presented 47 actions across 8 Key Areas. In this blog, CREU Director, and chair of the Expert Panel, Dr Noel Purdy, considers the opportunities and challenges ahead.

On 28th July 2020 when Education Minister Peter Weir MLA announced the establishment of the Expert Panel on Educational Underachievement in Northern Ireland, there was a broad welcome in principle that the Executive was seeking to address the issue and honour its New Decade New Approach commitment, but also a fair degree of frustration and scepticism on all sides at the prospect of yet another report on educational underachievement in Northern Ireland. In the Assembly debate following the ministerial statement SDLP MLA Dolores Kelly commended the Minister on his choice of the expert panel, but added that “it strikes me that he already knows a lot of the answers and findings that it is going to publish”. Later Sinn Fein MLA Karen Mullan spoke for many when she said it was “crucial that this panel goes beyond words, and outlines real and palpable actions that can be taken by the Minister to effectively address this issue.” PUP councillor Dr John Kyle noted that “Action plans to date have been piecemeal and short-term. A more comprehensive and sustained plan is necessary but this takes continued political commitment” while Prof Tony Gallagher of Queen’s University remarked that “rhetoric and promises are meaningless unless they are followed up by action and a new approach.” Simon Doyle, education correspondent of the Irish News, concluded that “rather than undertaking another costly, time-consuming review, the minister could easily act on the abundance of already-published information and recommendations”.

As chair of the Expert Panel, I understood this ‘report fatigue’ and was already familiar with the previous ‘un-actioned’ reports (e.g. Dawn Purvis’ Educational Disadvantage and the Protestant Working Class, 2011; John Kyle’s Firm Foundations, 2015; the Equality Commission’s Key Inequalities in Education, 2015; and Prof Ruth Leitch’s Investigating Links in Achievement and Deprivation (ILIAD), 2017) published over a decade and highlighting a wide range of issues including low levels of aspiration, low school attendance, academic selection, funding, early years investment, careers guidance, vocational education, economic investment, school leadership and the importance of forging stronger links with families and communities. However, while the body of evidence was substantial I believe that A Fair Start is different from previous reports in three key aspects and represents a once in a generation opportunity to address educational underachievement and inequality in Northern Ireland.

First, it is unique because of its inception as a cross-party commitment made by all 5 major political parties who signed up to the New Decade, New Approach political settlement of January 2020. Part 1 of the agreement set out the priorities of the restored Executive including the following commitment as an immediate priority:

The Executive will establish an expert group to examine and propose an action plan to address links between persistent educational underachievement and socio-economic background, including the long-standing issues facing working-class, Protestant boys

In Appendix 1 of the agreement, the education priorities for year 1 included the following:

Establish an expert group to examine the links between persistent educational underachievement and socio-economic background and draw up an action plan for change that will ensure all children and young people, regardless of background, are given the best start in life.

This may seem insignificant to some, but this raised the status of the Expert Panel’s work from the very start as an agreed cross-party educational priority, and also confirmed that this was not the work of one party or one community alone.

Second, A Fair Start is unique because, under the Terms of Reference, we were tasked with producing a costed action plan and, crucially, one which “must be deliverable in the current economic and political context” (p.2). Creating a costed action plan is a much more complex, challenging and time-intensive task than simply drawing general conclusions or writing a series of broad recommendations. To compound matters, the timeframe was demanding: 9 months from beginning to end. During this time the Expert Panel engaged in an extensive period of consultation through a call for written evidence (which attracted 400 responses), face-to-face or virtual engagement with 344 stakeholders (including school leaders, voluntary and community sector representatives, parents, government officials, MLAs, teaching unions, FE Colleges, children’s charities), two commissioned pieces of research/consultation with children and young people (facilitated by the National Children’s Bureau and Barnardo’s), and a detailed analysis of the most up-to-date statistics by Prof Demie. The panel also heard evidence from government departments from England, Scotland, Wales and the Republic of Ireland and read countless reports and policy documents.

Following this process of consultation, analysis of the existing evidence, consideration of the newly commissioned research and extensive deliberation, the Expert Panel published its final report and action plan A Fair Start on 1 June 2021. A Fair Start includes a total of 47 SMART actions across 8 Key Areas costed over the short term (1-2 years), medium term (3-4 years) and long term (5+ years). The level of projected annual funding builds up year on year as the various programme strands are developed and/or co-designed, reaching a total estimated annual expenditure of £73.1m by year 5 (2025/26). In the current economic climate, it is important to be able to justify such expenditure and so A Fair Start also includes explanatory notes to accompany each Key Area, setting out a rationale and providing referenced evidence from research.

A key message throughout is that we need to see the delivery of these actions as an investment in the future rather than an expenditure for today, hence the major Early Years focus (Key Area 1) through which we seek to create a seamless journey from pregnancy to pre-school, school and beyond, where every child is provided with the appropriate level of support needed in a timely and appropriate manner in order to realise their potential. The other Key Areas focus on championing emotional health and wellbeing, ensuring the relevance and appropriateness of curriculum and assessment, promoting a whole community approach to education, maximising boys’ potential, driving forward professional development of teachers and school leaders, and ensuring interdepartmental collaboration and delivery.

While it was considerably more difficult to produce a costed action plan than a series of broad recommendations, the result, I believe, is indeed a plan which is “deliverable”. As one senior official remarked, we have “made it easy” for officials to implement.

Third, I believe that A Fair Start is unique because it was endorsed by all 5 Executive parties on 27 May 2021, thus fulfilling the stipulation in the Terms of Reference that the Expert Panel should “focus on the wide range of issues on which consensus can be found” (p.2). Seeking consensus was another major challenge and we were very aware from the outset that although as a panel we were apolitical and sought to meet our stated objective to “ensure all children and young people, regardless of background are given the best start in life”, the outcomes would be read closely by all sides of the community, understandably keen to ensure that we showed no favour or bias. As a panel there was a determination from the outset to honour that objective, and I believe that we achieved it. That’s why, I believe, all 5 Executive parties have endorsed A Fair Start and it is also why it is crucial that all parties now follow through on this commitment in principle with a manifesto pledge to support the full implementation of the 47 actions.

The final two actions (in Key Area 8) set out a framework through which delivery of the Action Plan should be subject to oversight by an Implementation Committee chaired by the First Minister/Deputy First Minister and meeting biannually, and recommend that the Action Plan should be explicitly referenced within the next Programme for Government. These two final actions remain crucial to the implementation of the entire Action Plan and were very deliberately written in as 2 of the 47 actions. Six months to the day from its publication, there are encouraging signs that, rather than gathering dust like so many previous reports, the process of implementation of A Fair Start has already begun.

However, it is now imperative that all our local politicians work together, despite significant budgetary pressures, to seize this unprecedented opportunity to fully implement A Fair Start, resisting the temptation to settle for “cherry picking” or merely reaching for the “low hanging fruit” in the days to come. Following more than a decade of unrealised recommendations from numerous previous reports, and as we continue to deal with the many challenges of the Covid-19 pandemic (which has exacerbated existing social and educational inequalities), I am more convinced than ever that the impact of this Action Plan will be significant, promoting equity, fostering greater collaboration between schools, families and communities, closing the achievement gap, investing in the future and giving all of our children and young people ‘A Fair Start’.

To read A Fair Start and its Annexes, please follow this link.

The study, which was commissioned and funded by the TRC, aims to go ‘beyond the stereotype’ of the well-documented challenge of underachievement among Protestant working-class boys from disadvantaged inner-city communities, and to ‘cast the net wider’ to provide a broader and more representative picture. Particular challenges in rural communities, which have not been reported extensively to date in previous studies, are identified with some school leaders speaking of the difficulty in motivating boys to work hard towards GCSEs.

The study, which was commissioned and funded by the TRC, aims to go ‘beyond the stereotype’ of the well-documented challenge of underachievement among Protestant working-class boys from disadvantaged inner-city communities, and to ‘cast the net wider’ to provide a broader and more representative picture. Particular challenges in rural communities, which have not been reported extensively to date in previous studies, are identified with some school leaders speaking of the difficulty in motivating boys to work hard towards GCSEs.

Beyond the Stereotype is based on group interviews with principals, teachers and pupils in eight primary and post-primary schools in suburban, town and rural areas, and also with school governors and other leaders in those communities. The study aims to go ‘beyond the stereotype’ of the well-documented challenge of underachievement among Protestant working class boys in inner-city areas, and to ‘cast the net wider’ to provide a broader and more representative picture. It raises important questions about the purpose of education and how we measure success.

Beyond the Stereotype is based on group interviews with principals, teachers and pupils in eight primary and post-primary schools in suburban, town and rural areas, and also with school governors and other leaders in those communities. The study aims to go ‘beyond the stereotype’ of the well-documented challenge of underachievement among Protestant working class boys in inner-city areas, and to ‘cast the net wider’ to provide a broader and more representative picture. It raises important questions about the purpose of education and how we measure success.

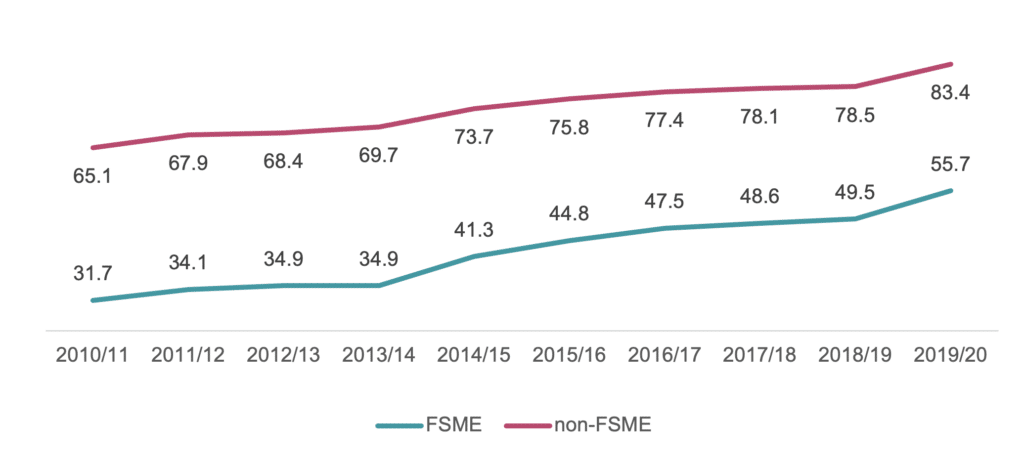

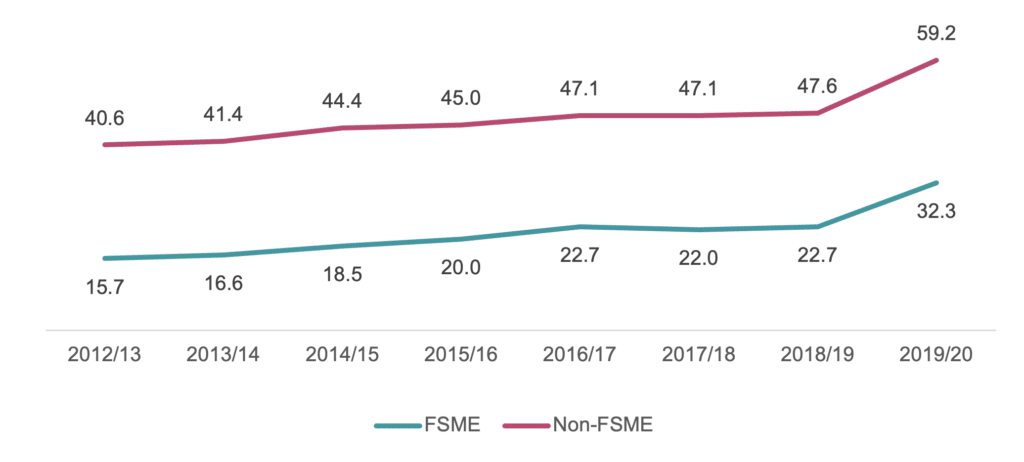

Taken at face-value, these data would indicate that the attainment gap did narrow in 2020, and therefore that rates of educational underachievement improved. It is clear that average grades increased significantly as a result of the use of centre-assessed grades, and it appears that FSME pupils benefitted slightly more than non-FSME pupils. Provisional GCSE statistics for 2020

Taken at face-value, these data would indicate that the attainment gap did narrow in 2020, and therefore that rates of educational underachievement improved. It is clear that average grades increased significantly as a result of the use of centre-assessed grades, and it appears that FSME pupils benefitted slightly more than non-FSME pupils. Provisional GCSE statistics for 2020  If the uplift in average A-level grades benefitted non-FSME pupils more than FSME pupils, it is unlikely that the opposite is true at GCSE, despite the impression we might get from the first graph (indicator 12). The closing of the attainment gap only appears evident in the 2020 data because proportionally more FSME pupils leave education at 16 and received their grade in 2020.

If the uplift in average A-level grades benefitted non-FSME pupils more than FSME pupils, it is unlikely that the opposite is true at GCSE, despite the impression we might get from the first graph (indicator 12). The closing of the attainment gap only appears evident in the 2020 data because proportionally more FSME pupils leave education at 16 and received their grade in 2020.