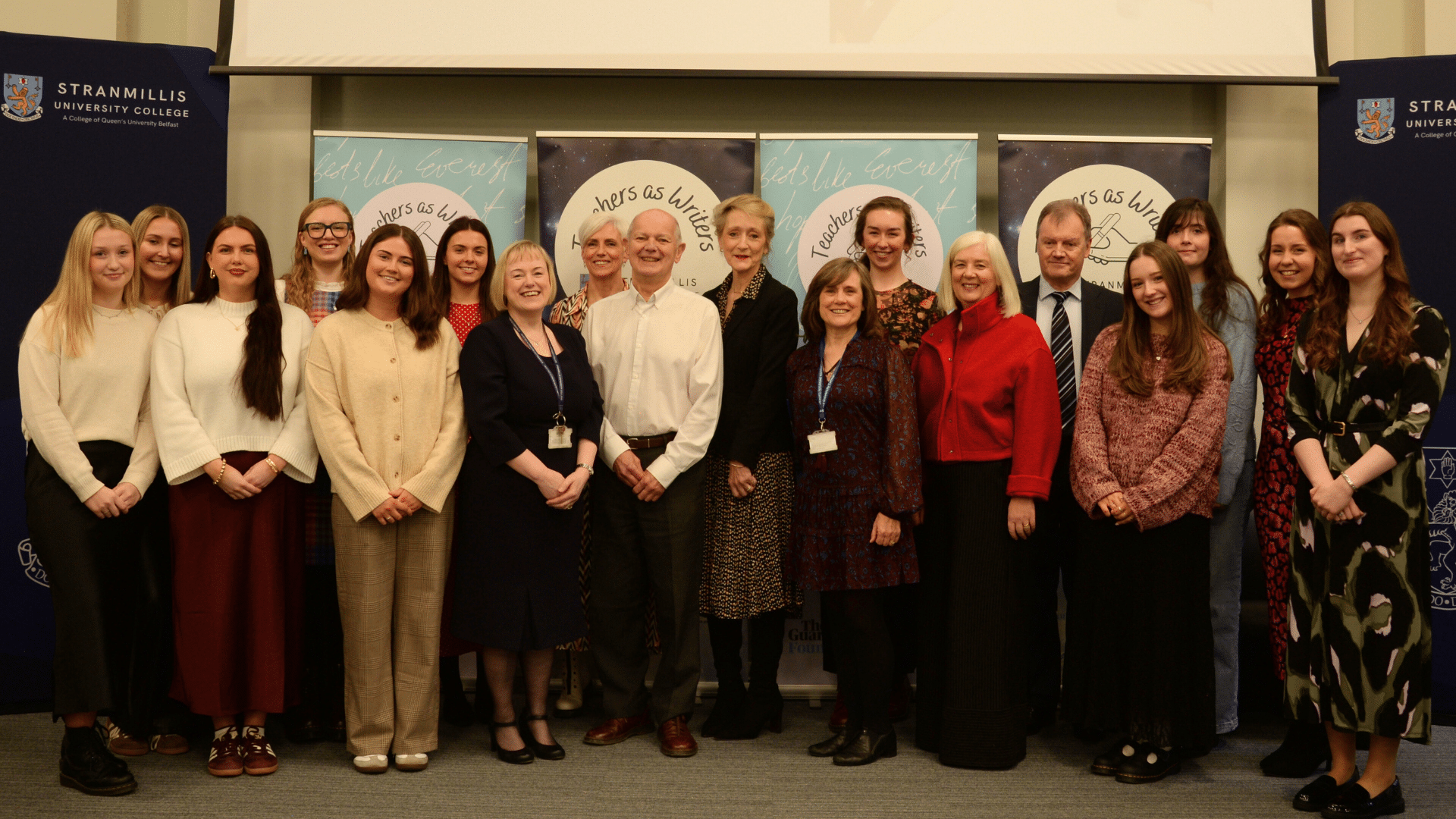

On 29 January, Stranmillis University College celebrated the importance of ‘Teachers as Writers’, in a special event showcasing creativity, confidence and classroom practice of student teachers with an audience of fellow students, school literacy leaders and academic experts.

The vibrant event, led by the Literacy team of lecturers Dr Gillian Beck, Diane McClelland, Dr Jill Dunn and Dr Sharon Jones, marked the launch of students’ writing in a series of publications, shining a spotlight on the imagination, craft and pedagogical insight developed across the College’s BEd Primary and Post Primary English programmes.

Through live readings and multimedia presentations, students shared their stories, poems and reflections on their creative journeys, demonstrating that having confident teachers who write sits at the heart of effective teaching and learning. The Literacy Team are very proud of what their students have achieved, both personally and professionally, and the impact that their writing continues to have on the children that they teach.

As part of the event, the College was delighted to also welcome keynote contributions from two leading figures in literacy and teacher education.

Prof David Waugh, Professor Emeritus at the University of Durham, reflected on his experience as a teacher, teacher educator and author, sharing insights from his work on literacy, inclusion and initial teacher education, as well as his unique experience of writing novels with groups of children.

Prof Teresa Cremin CBE, Professor of Education (Literacy) and Co-Director of the Literacy and Social Justice Centre at The Open University, explored research-informed approaches to reading and writing for pleasure. Drawing on her extensive body of work, she emphasised the importance of volitional reading and writing in shaping teachers’ and children’s literate identities.

The celebration took place during the UK’s National Year of Reading 2026, reinforcing the wider national focus on reading, writing and creative engagement.

Speaking at the event, Mr John McCusker (ETI) stated that, ‘Writing transforms children from being consumers of words to creators of worlds’, confirming the value of teachers who write and inspire children to do the same.

Dr Geraldine Maginness (DE; St Mary’s UC) congratulated the SUC Literacy Team and students on ‘their outstanding achievements, placing writing at the heart of their instruction’.

Dr Sharon Jones, senior lecturer in Education Studies at Stranmillis University College, will lead a creative writing workshop, Blogging for Joy, at Seamus Heaney HomePlace on Saturday 7 March.

Dr Sharon Jones, senior lecturer in Education Studies at Stranmillis University College, will lead a creative writing workshop, Blogging for Joy, at Seamus Heaney HomePlace on Saturday 7 March.

A new mixed-methods study funded by EPIC Futures NI and UKRI has highlighted significant challenges facing young people with special educational needs (SEN) as they transition from full-time school education into further education, training, employment or day-care provision in Northern Ireland.

A new mixed-methods study funded by EPIC Futures NI and UKRI has highlighted significant challenges facing young people with special educational needs (SEN) as they transition from full-time school education into further education, training, employment or day-care provision in Northern Ireland.

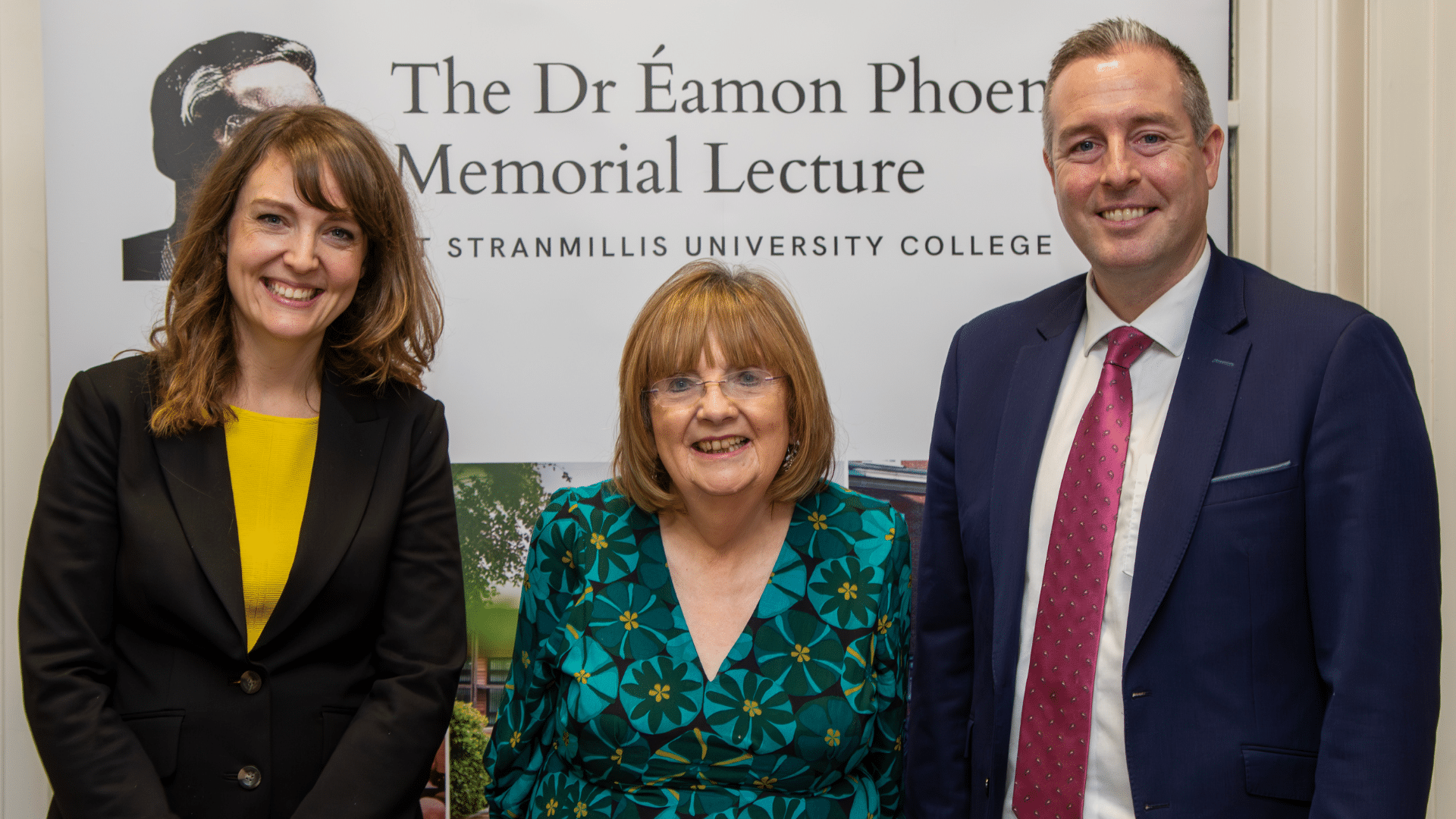

Prof. Noel Purdy OBE, Director of Research and Scholarship at Stranmillis University College, has been appointed to lead a major review of the Religious Education (RE) curriculum in Northern Ireland schools.

Prof. Noel Purdy OBE, Director of Research and Scholarship at Stranmillis University College, has been appointed to lead a major review of the Religious Education (RE) curriculum in Northern Ireland schools.