The sentiment of the popular inspirational acronym ‘Together Everyone Achieves More’ seems so simple that it could easily be dismissed as a platitude. Yet our current circumstances have brought the value of human togetherness into sharp focus. Our language reflects this too: the English word ‘teams’ has taken on a new dimension, now often referring to images of solitary figures in rooms contained in little boxes on a screen. Until the onset of Covid-19, sharing actual physical spaces with people outside our own homes was an accepted part of daily life. Our places of learning – nurseries, schools, colleges and universities – were particularly social in this respect. Almost without thinking about it, we shared classrooms and lecture theatres, assembly halls and staffrooms. The arrival of the pandemic disrupted this, and possibilities to spend time in common social spaces with family, friends, colleagues and students remain very limited. It has been said that it is not until we lose something that we realise how good it was. So what exactly have we been missing?

Body matters

Rowan Williams in his book Being Human: Bodies, minds, persons, argues that ‘Persons are more than ‘individuals’; they are both spiritual and material, and their uniqueness is fulfilled in community not in isolation and total independence’ (p. viii). Our bodies matter, as well as our minds: we are sensory. In a recent interview for the Irish Times, Irish philosopher Richard Kearney described the Covid-19 pandemic as an ‘attack on the senses’. This is of course true in a very real way for those who have experienced the loss of taste and smell as a symptom of the Covid-19 virus. But it is also true that the pandemic has accelerated the shift from being together physically with other people to communicating virtually. This change had already been ushered in by the digital revolution. There are multiple examples of technology enhancing many aspects of our lives in recent years, not least in education. Schools in Northern Ireland have harnessed the benefits of digital innovation in a particularly admirable way. Interestingly though, Kearney argues that over the past year the speed of the shift has prioritised, and perhaps overloaded, our sense of sight, while at the same time inhibiting our sense of touch. This imbalance is a matter of concern. As Kearney puts it ‘It is no accident that skin is our largest organ … We need computers but we also need carnality.’

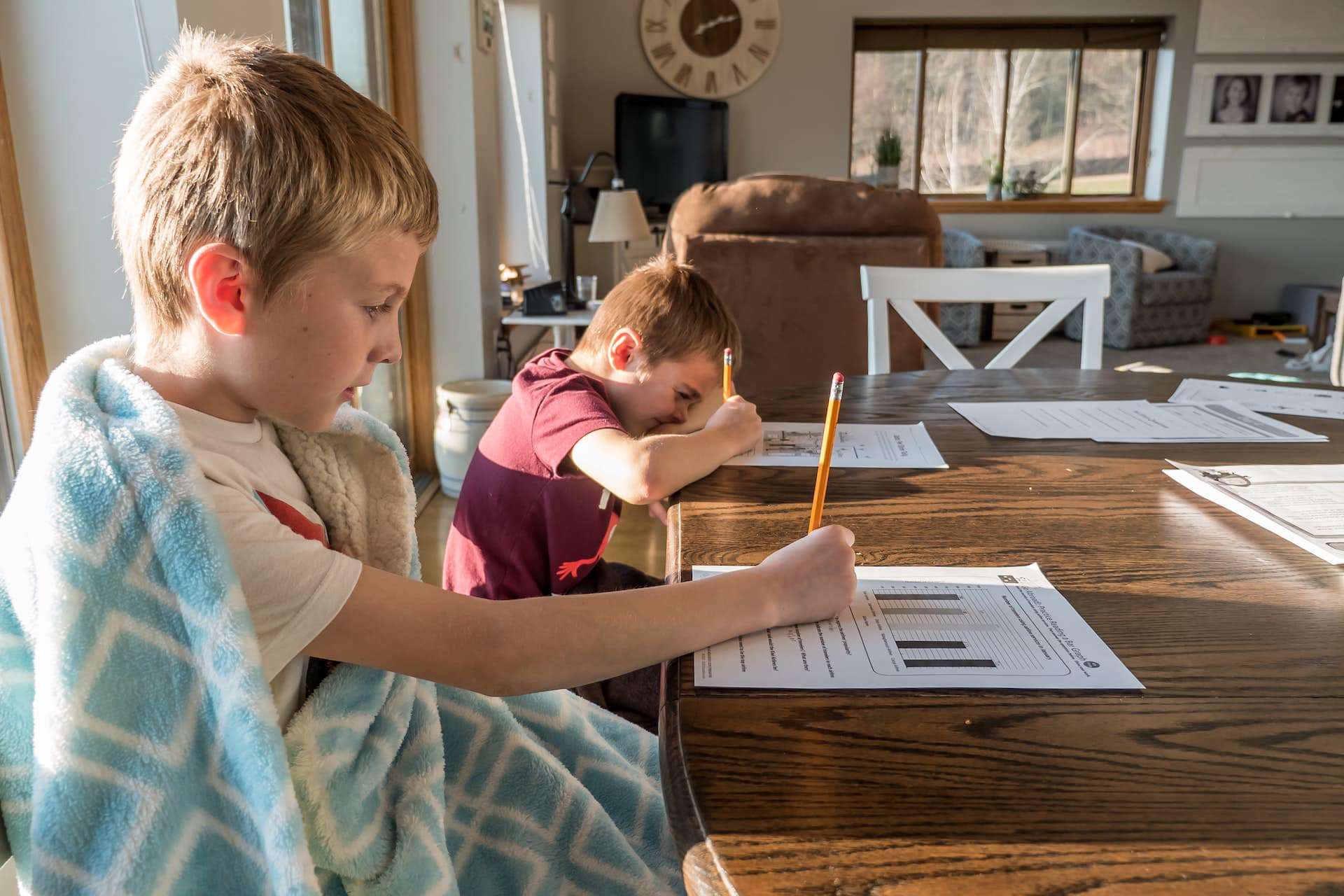

Hands on learning

In Kearney’s view, tangibility, or being close enough physically to touch another person or thing renders us vulnerable as human beings, but it also makes us more receptive to other people and our wider environment. This is particularly important in the learning of young children in play as Glenda Walsh and John McMullen have highlighted. We know all too well that touch can cause injury and harm, but over centuries, touch has also been a source of healing. It is by reaching out and engaging with other people and our surroundings at close quarters that we learn, that we learn to communicate, and that we develop empathy. By being close to people we can begin to read them, rather like a book. This is an important aspect of our being, and it is needed for us to flourish.

Mind matters too

Human beings, according to Rowan Williams, are both spiritual and material. Similarly, health is not simply either mental or physical, but embraces the whole person. There are real and valid concerns around physical contamination by a potentially dangerous virus, and these require a concerted response. But they need to be balanced by concerns for health more broadly, and particularly by an awareness of mental health. In a recent blog Noel Purdy highlighted the need to promote emotional health and wellbeing among young people especially. As lockdowns continue across the globe, concern for mental health generally is growing. For example, according to a recent study reported in the Lancet, ‘the increase in probable mental health problems reported in adults also affected 5–16 year olds in England, with the incidence rising from 10·8% in 2017 to 16·0% in July 2020 across age, gender, and ethnic groups’.

The focus of governments has turned in recent weeks to children and young people going back to school. There has been talk of lost months and years of education, identifying learning gaps, catch-up plans and reducing school holidays. In the middle of all this we shouldn’t lose sight of what it is to be human. For according to Rowan Williams, ‘Unless we have a coherent model of what sort of humanity we want to nurture in our society, we shall continue to be at sea over how we teach’ (p. x).

On being human … together

Absence might make the heart grow fonder, but spending time with each other in a shared physical space is a vital part of healthy human development and relationships. Not being together has made lockdown periods very difficult for many people, and young people in particular have found that being apart makes friendships very difficult. Research has also shown that face to face social interaction results in better learning. For example, in language acquisition, Patricia Kuhl’s 2003 early childhood study found that ‘infants show phonetic learning from live, but not pre-recorded, exposure to a foreign language’. Teachers need to spend time face to face with their students. To create learning opportunities that are really valuable we need to get to know peoples’ needs and preferences. And we need to spend time together, talking and listening.

From Zoom to room

There is something of a sense of déjà vu (see last year’s blog) as yet again, we face the prospect of going back to school. The challenges involved in moving from Zoom to room are real. But so are the potential rewards: physical, mental and spiritual. People of all ages are trying to make sense of our world’s complexities and of strangeness of the days and nights that we have known. For this reason, many believe that as far as education is concerned, a playful, nurturing approach will be vital for children and young people, with language and communication, one of its 6 core principles, at its heart. In Northern Ireland it is encouraging to see signs of a commitment by government to this, with funding allocated to a new Nurture Programme.

Experiences of pandemic lockdown have gifted us with a greater awareness of the benefits of technology to keep us connected digitally. But we have also come to understand, perhaps more fully than at any point in history, that isolation from each other physically is unhealthy. Perhaps what we need most is getting back to exactly what we have been missing: being together.

Dr Sharon Jones is a Stranmillis University College Lecturer and member of the Centre for Research in Educational Underachievement

A team from Stranmillis University College’s

A team from Stranmillis University College’s