Today a phased return to school begins for some children. While most weary parents, passionate teachers and isolated pupils agree that a full return is needed for all pupils, there are concerns about timing and the practicalities that schools and parents will now face.

Much of the media discussion has surrounded whether or not children are ‘super-spreaders’. A PHA presentation to education officials suggested that Schools are not a ‘major source’ of transmission. It is vital, however, that this discussion is counterbalanced by consideration of the negative impact of long-term school closures and the subsequent isolation of our children and young people. The negative impact of lockdown on their mental health and wellbeing is becoming clear in research from previous school closures, in practice, in our own experiences and in our conversations with family and friends. This impact is exacerbated by the closure of their other face-to-face social networks outside of school- such as sports clubs, youth clubs and societies.

As a trustee of Links Counselling Service I (John) am acutely of the mental health impact of lockdown throughout society. With many community resources unavailable, we are overwhelmed with self-referrals, GP referrals and signposting from other services. Our waiting list, including children aged 4-18, has more than doubled from a year ago despite a larger workforce that ever before. COVID-19 has not only exacerbated pre-existing mental ill health among individuals, families and communities, it has greatly challenged the systems in place to care for them.

Another balancing act

Balance is also needed is within the public (and media) discourse about children’s mental health. While there is clearly cause for concern, we need to avoid fatalism when it comes to our children. This is not the ‘COVID generation’ forever damaged by a ‘tsumani’ of mental health problems, as some of the more dramatic headlines would have you believe. Recent research from the University of Oxford, reported an increase in emotional, attentional and behavioural issues during the first lockdown period. Reassuringly, these issues decreased when lockdown was lifted, but with increased restrictions these issues have re-emerged. This places an emphasis on decision makers to ensure that lockdown restrictions that impact on children and young people are kept as short-term as possible.

However, a deterministic and fatalistic discourse can be counter-productive, cultivating a self-fulfilling prophecy that paralyses systems and prevents them from fully committing to the support that is needed to recover. Our children are so much more than the pandemic they have lived through. They have demonstrated creativity, kindness and resilience. It’s important to remain hopeful and to help our young people to find hope when they are worried about the future. It is the balancing act of our time to hold both of these realities together; that many people are struggling, and that things can get better.

Resilience Resides in Relationships

We often hear it said that ‘children are resilient’, but the truth is a little more nuanced. Psychologists define resilience as the process of adapting well in the face of adversity or significant sources of stress. Resilience means ‘bouncing back’ from difficult experiences, but it also means being empowered to grow and even improve your life along the way. Research has moved away from seeing resilience as a trait that people do or don’t have. There are various individual psychosocial factors that impact resilience levels, but there is also emerging evidence of a bidirectional relationship between healthy communities and more resilient individuals. This is important. It means resilience can be promoted and developed, and schools can play a role in this.

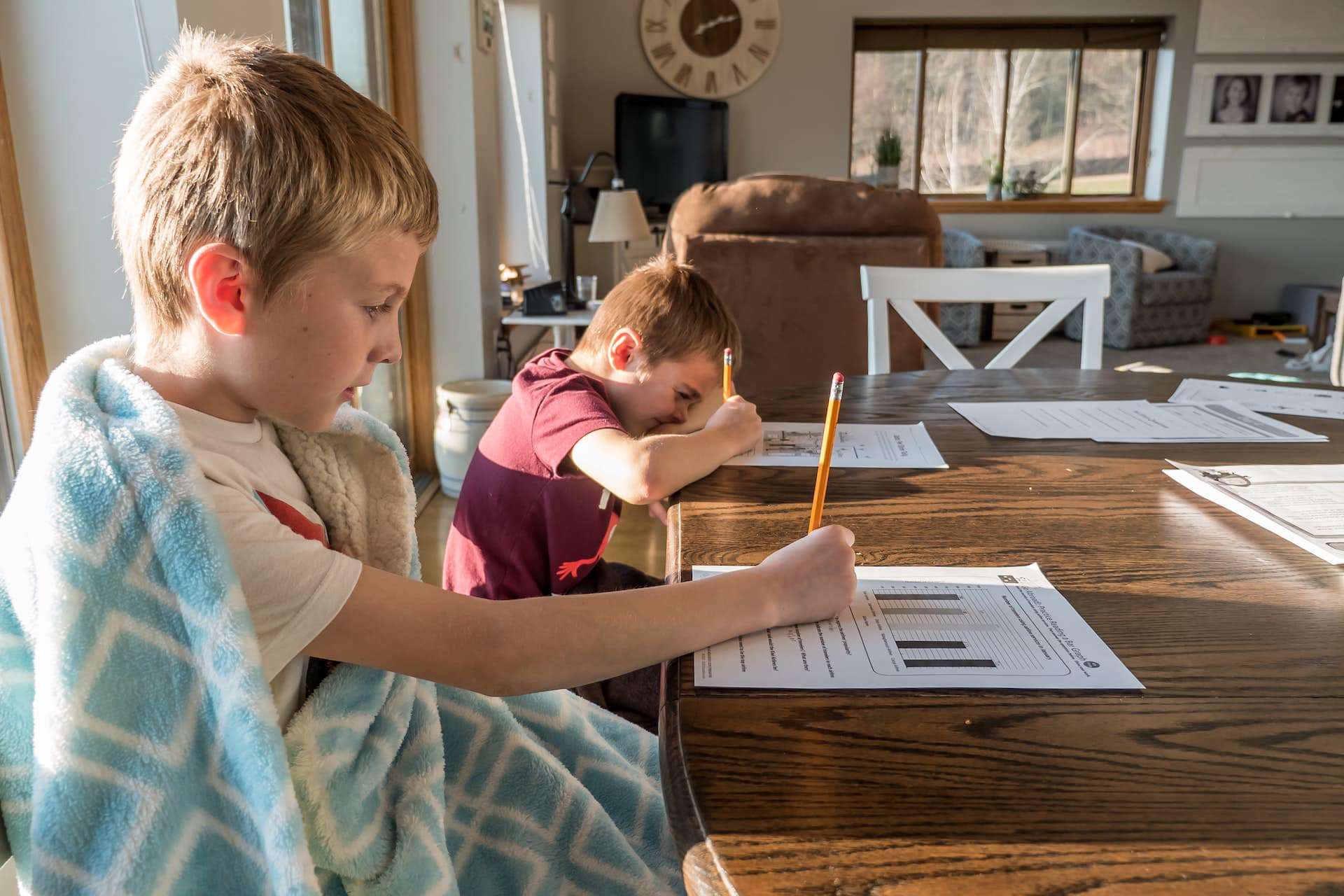

The majority of kids won’t need counselling post-lockdown. They will benefit from getting back to the structured, stable and secure environment of school. The predictable routine, clear expectations and consistent rules help children to feel safe. Then, most importantly, they will need space to play and to reconnect with others. Research also emphasises the important link between children engaging in sport and physical activity and their wellbeing. We need to see a return to these activities too.

Psychiatrist Bruce Perry states that, because humans are inescapably social beings, the worst catastrophes that we can experience are those that involve relational loss. Therefore, recovery must involve re-establishing human connections.Perry states that the most important healing experiences often occur outside therapy and inside homes, schools and communities. Before ‘catching up’ on missed learning we need to let the kids catch up with each other, and with staff. Resilience resides in relationships.

Through relationships we can reassure children that they are experiencing normal reactions to abnormal events. We can help them, as the Dr Marie Hill has outlined, to emotionally regulate before we educate. Prof Barry Carpenter and colleagues have developed practical resources for a Recovery Curriculum that encourages a systematic, relationships-based approach to teaching and learning post-lockdown. This is an example of the creative and systemic approach required to support our children and young people.

That said, every child and young person will come through this differently and there will be a range of responses needed. While all might need something extra, some will need more ‘extra’ than others. Lockdown has exacerbated disadvantage and pre-existing vulnerability. Some young people will need additional systemic and therapeutic support to prevent more severe mental ill health down the line. It’s vital that long-term planning includes improving availability and accessibility of this support.

Ultimately, we need to trust our teachers and school leaders to know how to best support our children post-lockdown. We need to embrace their professional capacity, support the system where we can, and lobby to ensure that they are properly resourced. It is essential that we prioritise children and young people as we emerge from this pandemic. They have been asked to make huge sacrifices and it is now time that we uphold their rights for equitable access to education, play and social development.

Dr John McMullen is an Educational and Child Psychologist, and a Senior Lecturer at Stranmillis University College and Queen’s University Belfast.

Dr Victoria Simms is the Director of Research in the School of Psychology, Ulster University, and is an expert in child development.