Last week, pupils across Northern Ireland received their GCSE and A-level grades – the culmination of two years of work and learning that have been significantly disrupted by the Covid-19 pandemic. Headlines focused on the rise in top grades awarded and the use of teacher-assessed grades, however we at the Centre for Research in Educational Underachievement are keen to understand what the available data can tell us about how the GCSE and A-level attainment gap has been affected by the pandemic.

In a September 2020 blogpost I predicted that “if we were to consider final grades alone, 2020 will superficially appear as a highly successful year in the Northern Ireland Executive’s long-standing commitment to tackling Educational Underachievement”. In May, the release of the latest edition of “Qualifications and Destinations of Northern Ireland School Leavers 2019/20” by the Department of Education (DE), appeared to indicate that this indeed was the case. These data have been used for several years, according to the release, to “inform a wide range of policy areas aimed at raising standards and tackling educational underachievement”. They are used by “policy teams … across the education service”, “are used to respond to Assembly questions”, and “are included in the Department’s accountability and performance management process”. As such, these data represent the best available information for research and policy relating to educational underachievement in Northern Ireland. They feed into the highest levels of policy accountability through the Executive’s Outcomes Delivery Plan and particularly its Indicator 12: the gap between the percentage of non-FSME school leavers and the percentage of FSME school leavers achieving at Level 2 (GCSE) or above including English and Maths. In this blog, we argue that this data release can only provide misleading, half-answers to our question: “did the attainment gap narrow in 2020?”, and should be improved in order to better serve education policy in Northern Ireland.

A disclaimer was added to this year’s release, acknowledging that the way that GCSE and A-level grades were awarded in 2020 was very different to normal years, as well as many other qualifications:

“given the new method of awarding grades in 2019/20, caution should be taken when drawing any conclusions relating to changes in student performance. Year-on-year changes might have been impacted by the different process for awarding qualifications in 2019/20 rather than reflecting a change in underlying performance”.

Whilst this disclaimer confines itself to the technical detail of the awarding of qualifications, it also serves as a reminder of the wider impacts of the pandemic on education, which were unequally felt across the population. Whilst consistent attainment data prior to GCSE is not currently available for Northern Ireland, systematic studies in England identified a loss of learning across age groups and across the curriculum, which was roughly tripled for children eligible for Free School Meals (FSME). Our own research with parents and carers across Northern Ireland in both 2020 and 2021 found that children in disadvantaged households were spending less time learning, and that their parents were less confident teaching them. However – positive steps were also taken during this time, with the release of extra funding to supply low-income families with digital devices for learning and for catch-up programmes, and many inspirational examples of teacher networking, mutual support and upskilling in the use of blended learning. Having some idea of the effects of these unprecedented challenges and remedial interventions on the socio-economic attainment gap is vital as the education system continues to adapt and recover from the pandemic, to avoid further widening of educational inequalities.

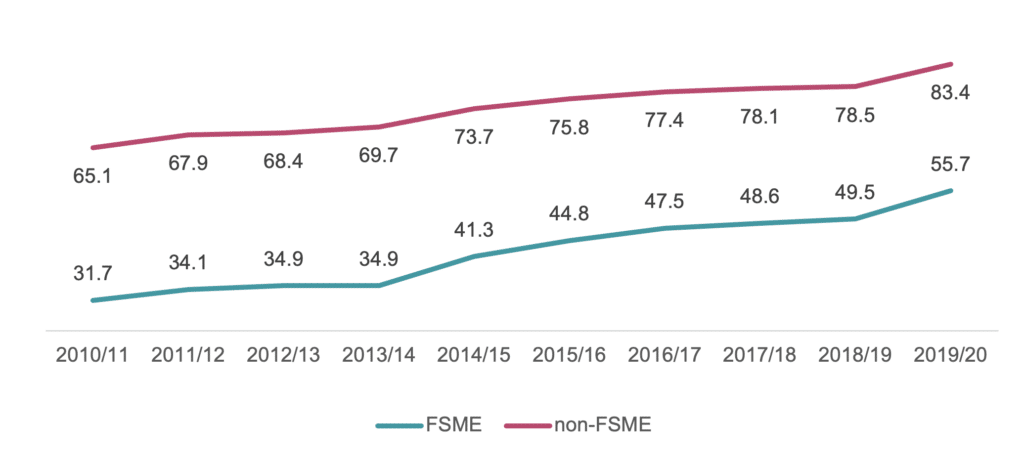

What the data says about the GCSE attainment gap

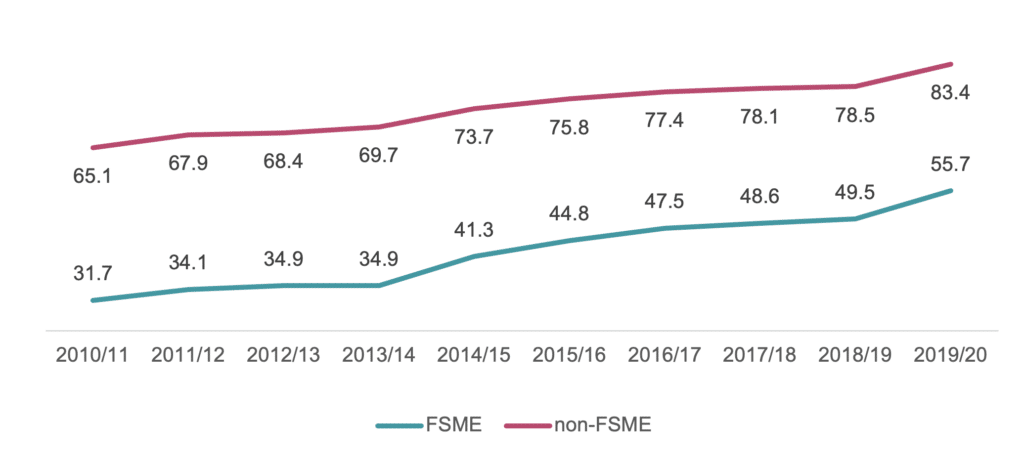

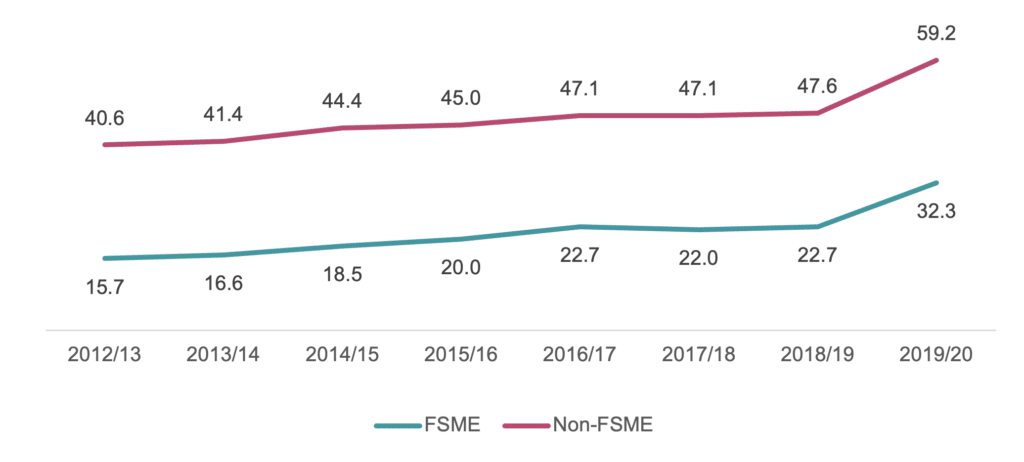

So, did the attainment gap narrow in 2020? The graph below plots GCSE or equivalent (Level 2) attainment amongst FSME and non-FSME school leavers (Indicator 12), as reported in the school leavers survey data release over the past ten years. The increase in average grades appears to have benefitted FSME pupils slightly more than non-FSME pupils in this metric, closing the gap between them from 29 percentage points in 2018/19 to 27.7 percentage points in 2019/20.

% non-FSME school leavers and % FSME school leavers achieving at Level 2 or above including English and maths, School Leavers’ Survey 2019/2020

Taken at face-value, these data would indicate that the attainment gap did narrow in 2020, and therefore that rates of educational underachievement improved. It is clear that average grades increased significantly as a result of the use of centre-assessed grades, and it appears that FSME pupils benefitted slightly more than non-FSME pupils. Provisional GCSE statistics for 2020 released by CCEA suggest that the percentage of GCSEs awarded C or above increased by 7.5 percentage points in 2020, having remained roughly stable since 2016.

Taken at face-value, these data would indicate that the attainment gap did narrow in 2020, and therefore that rates of educational underachievement improved. It is clear that average grades increased significantly as a result of the use of centre-assessed grades, and it appears that FSME pupils benefitted slightly more than non-FSME pupils. Provisional GCSE statistics for 2020 released by CCEA suggest that the percentage of GCSEs awarded C or above increased by 7.5 percentage points in 2020, having remained roughly stable since 2016.

Upon closer examination, however, we see that the data underpinning this picture are misleading. The extent to which the attainment gap was narrowed by the new method of awarding grades is obscured by the fact that each year school leaver survey data includes a large number of pupils who left school in 2020 at the end of Year 13 or 14 and therefore sat their level 2 exams one or two years prior. A rough estimate based on numbers of school leavers with A-levels as opposed to GCSEs as their highest qualifications reported in the release, suggests that two-thirds of school leavers fall into this category. For 2019/20, this means that most school leavers sat their exams in ‘normal’ pre-covid circumstances. These pupils, who according to the same data are more likely to be non-FSME, won’t have benefitted from the 2020 uplift. As such, it may be that much of the closing gap observed in the graph above is due to this discrepancy. This effect will be present in this data for at least the next three years, but it is difficult to know its magnitude as the release gives only a proxy indication of the numbers leaving school at the end of year 12, 13 and 14. Furthermore, as DE has suspended the annual Summary of Annual Examination Results (SAER) for 2019/20 and 2020/21, no other administrative data will be available on Key Stage 4 achievement for corroboration during this period.

What about A-level grades?

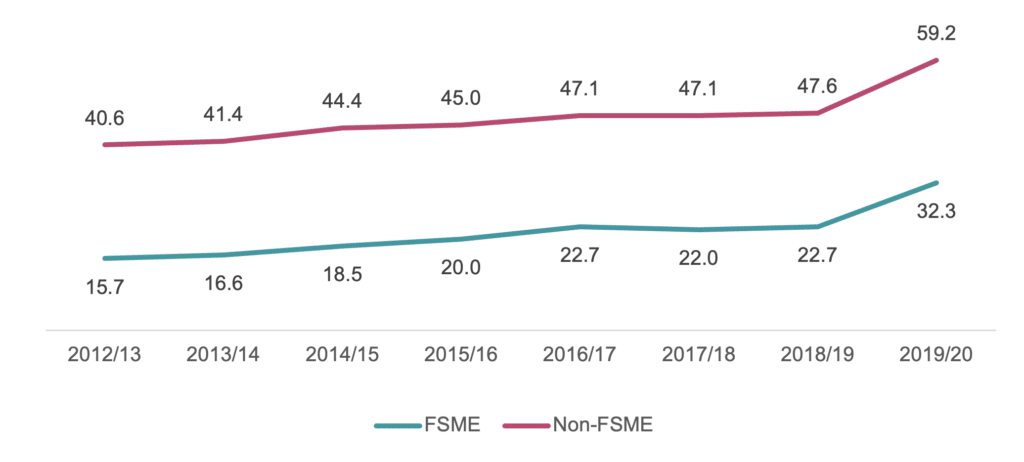

The point can be further supported by turning our focus to A-level grades as reported in the 2019/20 school leavers’ data, almost all of which will have been awarded in 2020. Here the increase in the percentage of students achieving the benchmark of 3 or more A-levels A*-C is significantly greater than with the Level 2 benchmark. However, we now see that the increase for non-FSME pupils exceeded the increase for FSME pupils by two percentage points, widening the attainment gap by as much.

% non-FSME school leavers and % FSME school leavers achieving 3 or more A-levels A*-C

If the uplift in average A-level grades benefitted non-FSME pupils more than FSME pupils, it is unlikely that the opposite is true at GCSE, despite the impression we might get from the first graph (indicator 12). The closing of the attainment gap only appears evident in the 2020 data because proportionally more FSME pupils leave education at 16 and received their grade in 2020.

If the uplift in average A-level grades benefitted non-FSME pupils more than FSME pupils, it is unlikely that the opposite is true at GCSE, despite the impression we might get from the first graph (indicator 12). The closing of the attainment gap only appears evident in the 2020 data because proportionally more FSME pupils leave education at 16 and received their grade in 2020.

How could the available data be improved?

In sum, this data release can only provide unclear, incomplete and inaccurate answers to the question “did the attainment gap narrow” in any given year. This crucial question lies at the heart of the Outcomes Delivery Plan’s indicator 12, and so we would contend that, given the uncertainties highlighted above, this data release does not serve its purpose to “inform a wide range of policy areas aimed at raising standards and tackling educational underachievement” and this is particularly the case in relation to the Level 2 (GCSE or equivalent) results which are most often cited as the key measure of educational achievement in Northern Ireland. The release would be greatly improved if it were to provide an accurate breakdown of the number/percentage of pupils represented within each year group, and this breakdown should be reflected in Indicator 12 statistics.

Of course, there may be several other policy areas and indicators that we have not considered here that are equally ill-served by this data. A clear implication of this conclusion is that a more comprehensive range of measures and available data are needed for effective policymaking and accountability. England’s National Pupil Database, which since 1996 has provided detailed, individual pupil data for research and policymaking, should serve as an example. Such data not only allows for accurate, disaggregated analysis of the impacts of policies and interventions, it also avoids duplication of data collection efforts by researchers and government departments. It can also be powerfully linked to other administrative data such as census, health, and employment data – something that has been explored recently in Northern Ireland to explore patterns of GCSE attainment. The recent Action Plan of the expert panel on Educational Underachievement in Northern Ireland (A Fair Start) indicated that a forthcoming System Evaluation Framework in preparation at DE will make progress in this area, and argued that it must include the standardised collection of Key Stage 1-3 cohort data as well as more accurate measures of attainment at GCSE and A-level (or equivalent). Past failure to achieve consensus with teaching unions and schools should not stand in the way of progress in this area, which is it vital to understanding the true nature and extent of educational underachievement (especially post-covid) and to tackling it effectively.

The ongoing challenge for government, and for schools, is not only to keep on closing the attainment gap, but to do so in a way that is meaningful in terms of ensuring quality educational opportunities for all to create a more equal society. To do this, we will need better data, which will necessitate the allocation of adequate resources and require schools, teaching unions and government to reach a consensus.

Dr Jonathan Harris is the Research Fellow at the Centre for Research in Educational Underachievement

The study, which was commissioned and funded by the TRC, aims to go ‘beyond the stereotype’ of the well-documented challenge of underachievement among Protestant working-class boys from disadvantaged inner-city communities, and to ‘cast the net wider’ to provide a broader and more representative picture. Particular challenges in rural communities, which have not been reported extensively to date in previous studies, are identified with some school leaders speaking of the difficulty in motivating boys to work hard towards GCSEs.

The study, which was commissioned and funded by the TRC, aims to go ‘beyond the stereotype’ of the well-documented challenge of underachievement among Protestant working-class boys from disadvantaged inner-city communities, and to ‘cast the net wider’ to provide a broader and more representative picture. Particular challenges in rural communities, which have not been reported extensively to date in previous studies, are identified with some school leaders speaking of the difficulty in motivating boys to work hard towards GCSEs.

Taken at face-value, these data would indicate that the attainment gap did narrow in 2020, and therefore that rates of educational underachievement improved. It is clear that average grades increased significantly as a result of the use of centre-assessed grades, and it appears that FSME pupils benefitted slightly more than non-FSME pupils. Provisional GCSE statistics for 2020

Taken at face-value, these data would indicate that the attainment gap did narrow in 2020, and therefore that rates of educational underachievement improved. It is clear that average grades increased significantly as a result of the use of centre-assessed grades, and it appears that FSME pupils benefitted slightly more than non-FSME pupils. Provisional GCSE statistics for 2020  If the uplift in average A-level grades benefitted non-FSME pupils more than FSME pupils, it is unlikely that the opposite is true at GCSE, despite the impression we might get from the first graph (indicator 12). The closing of the attainment gap only appears evident in the 2020 data because proportionally more FSME pupils leave education at 16 and received their grade in 2020.

If the uplift in average A-level grades benefitted non-FSME pupils more than FSME pupils, it is unlikely that the opposite is true at GCSE, despite the impression we might get from the first graph (indicator 12). The closing of the attainment gap only appears evident in the 2020 data because proportionally more FSME pupils leave education at 16 and received their grade in 2020.