If we were to consider final grades alone, 2020 will superficially appear as a highly successful year in the Northern Ireland Executive’s long-standing commitment to tackling Educational Underachievement. As with the other administrations in the UK, average GCSE and A-level grades have risen significantly since 2019, following the cancellation of formal exams and belated government decisions to award grades based on teacher predictions rather than those produced by controversial algorithms (unless the latter was higher). The proportion of pupils achieving the benchmark of 5 GCSEs at C grade or above has certainly increased. When full details of these statistics are published by the Department of Education, it will be interesting to see what effect this general bump-up in grades will have had on the various ‘attainment gaps’; between boys and girls, between FSME and non-FSME pupils, and between pupils of different religious/community backgrounds. Although the full picture is not yet clear, the controversy over A-level and GCSE grades points to a fact worth remembering even in ‘normal’ years: our system of examinations and grading is designed to produce a spread of outcomes, and plays a part in re-producing patterns of what is perceived as educational underachievement.

In their article entitled ‘What is ‘underachievement’ at school?’ Stephen Gorard and Emma Smith wrote that in education policy and practice, underachievement can mean one of three things: low achievement, below a particular benchmark; lower achievement than would be expected by the observer; and lower achievement of one group or individual relative to another. As such, underachievement is intrinsically related to standard assessments that invite comparison across the population – particularly GCSEs and A-levels.

What do grades mean?

This year, more than ‘normal’ years, concerns have been repeatedly raised about how ‘meaningful’ the grades students receive are. They are important for employers and higher education institutions attempting to make a selection from a pool of applicants for limited places. They are also important for the governance of the education system, for governments and schools to measure their performance against previous years. The fear of ‘grade inflation’ has shone a spotlight on the role of exams regulators, and the entirely normal practice of moderation and the adjusting of grade boundaries to maintain a distribution of grades that is broadly comparable to previous years. Put simply, the fact that many students achieve grades below a C does not indicate a widespread problem of educational underachievement – it is the way the system is designed to work. Despite a nominally criterion-referencing system of grading, where in theory every candidate can achieve a passing grade if they demonstrate the required level of knowledge or skill, in reality marks are always moderated and/or standardised to produce a spread of grades. What has been highlighted this year is how arbitrarily an individual student might have their marks revised downward, particularly if they are perceived as ‘overachieving’ in relation to their school’s performance history. In normal years, moderation is applied to non-examined assessments (NEAs) in this way, and standardisation applies across the board. This perpetuates downward pressure on the likely attainment of disadvantaged pupils, widening the gap between their grades and those of their more advantaged peers who are more likely to request and obtain a re-mark that will revise their grade upwards. Such practices are justified on the basis that a) pupils’ grades should be broadly comparable to the cohorts of previous years, and b) that universities and others need to be able to fairly allocate limited places to applicants. However, the former imperative reduces the likelihood of disadvantaged students ‘breaking through’ and the latter builds inequality of outcomes into the education system as a necessity. This isn’t objectively unfair, but neither is it objectively fair – rather it is a political judgement passed off as a technically unavoidable problem.

Whose grade is it anyway?

The recent controversy has also broken down the widely held assumption that an individual pupil’s grade belongs solely to them. In a ‘normal year’ standardised public exams are meant to provide a way for an individual pupil to demonstrate their own individual competence in a given discipline by ‘taking the test’ – with no outside help allowed. The recent removal of controlled assessments (coursework) from GCSEs has served to make this individualization more acute, as the pupil is, in theory, removed from the ‘unfair’ help of their teachers, parents, friends and tutors. The absence of these tests taking place in 2020 has highlighted that GCSE and A-level grades belong not only to individual pupils, but also to their teachers, to their schools and ultimately to their governments (via independent exams regulators). Basing pupils’ grades on teachers’ predictions has been attacked on the basis that teachers and schools will inflate their pupils’ grades to game estimates of their own performance. The stakes are high, as teachers and schools perceived as underperforming may be subject to punitive managerial measures or a lack of applicants in future years. Schools with disadvantaged intakes were particularly likely to be downgraded by the algorithms of Ofqual and CCEA on the basis that their estimates were too far above the historical average for their school. Such is the power of this accountability regime, that the initial attempts to award grades through algorithms focused on parity with previous years on a national scale and at the scale of the school, whilst individual grades could be wildly different from pupils’ and teachers’ expectations. As Jon Andrews of the Education Policy Institute has pointed out,

“we had ministers celebrating the fact that A level results had only increased by a couple of percentage points, that standards had been maintained. But this was not a model that needed to work at a national level, it needed to work for hundreds of thousands of individuals in thousands of schools. It does not matter if your total number of grades is correct if a large number of them have been assigned to the ‘wrong’ candidates.”

If we recognise that a pupil’s grade belongs not only to themselves but to their teachers, their schools and their governments, who are in some way held accountable for the grades their pupils attain, then we may be able to critically re-examine educational underachievement and understand that it cannot be ‘solved’ under the current system of exam-driven selection for teacher/school accountability and options for higher education and employment.

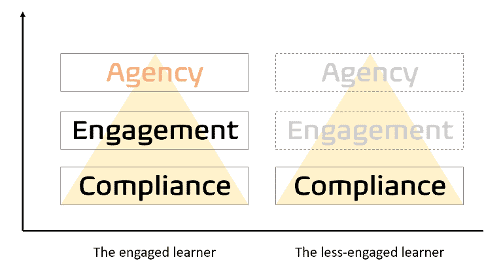

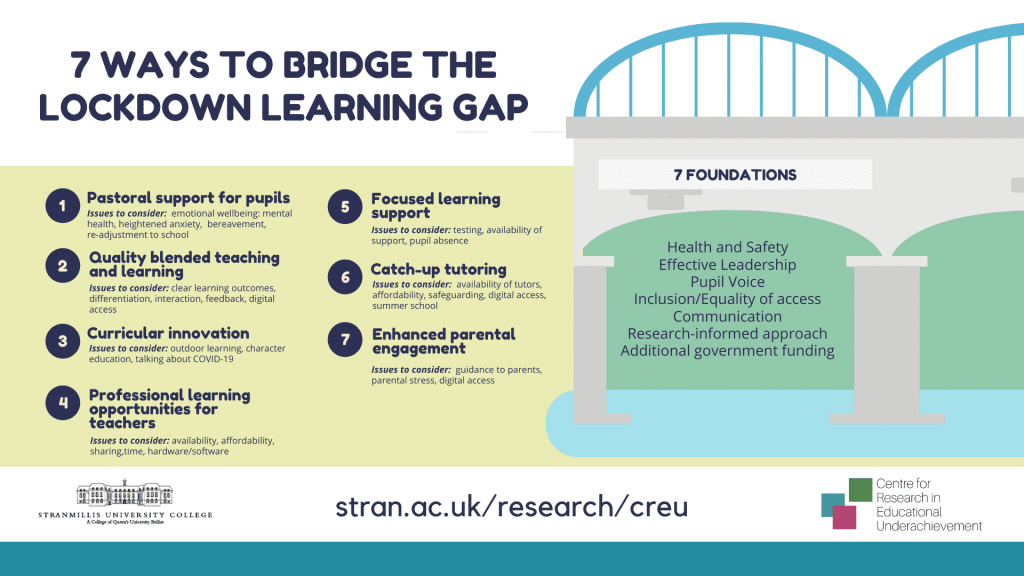

However, this is not to say that nothing can be done, rather that our perspective on what constitutes achievement in education must be broader than the grades pupils obtain aged 16 and 18. This might mean abandoning standardisation in favour of true criterion-referencing, so that fewer young people are necessarily branded as ‘underachievers’. It might mean disconnecting accountability regimes from these grades, and thereby allowing them to ‘belong’ entirely to the pupil, whilst teachers and schools’ success is measured in another, less easily quantifiable way. There is no unshakeable rule that schools must be made to compete with one another on the basis of grades in order to improve standards. Could a teacher or school’s performance be assessed through criterion-referencing, rather than the zero-sum game of absolute competition embodied in league tables and England’s new Progress-8 scoring system? Of course, parents and the press might continue to fixate on league tables, but accountability measures can and should take a different approach. At the Centre for Research in Educational Underachievement we take this attitude forward in our qualitative work, which valorises the voices of pupils and foregrounds early years and primary education as an arena for meaningful progress in bringing about greater social justice through education.

Dr Jonathan Harris is the Research Fellow at the Centre for Research in Educational Underachievement